An Example of Open Source Drug Discovery

“Open Source Drug Discovery? How does that work?” I am asked this quite a lot. There are some principles and core practices that are involved, embodied in the Six Laws, but those are quite hifalutin. Let me give a practical example.

The main point is that everything is open, so anyone can come along, make molecules, do biology, do informatics, contribute data to the lab notebooks, coordinate the research and generally contribute in any number of ways for which there are simple technological solutions. All sorts of inputs are possible, including experimental ones.

Earlier this year there was a need to make a bunch of molecules as part of the first medicinal chemistry campaign in the open source malaria project. The hit molecule that was the starting point had an ester in it, and initial results had shown that the ester was a problem. There were several ester replacements that needed to be synthesized. Many of these had been made. A few had either not been tackled or were proving difficult to make. Alice Williamson made up a “Wanted” poster to highlight that anyone could have a go at making them (see below, and in these nice images of the process of collaboration that Alice also made).

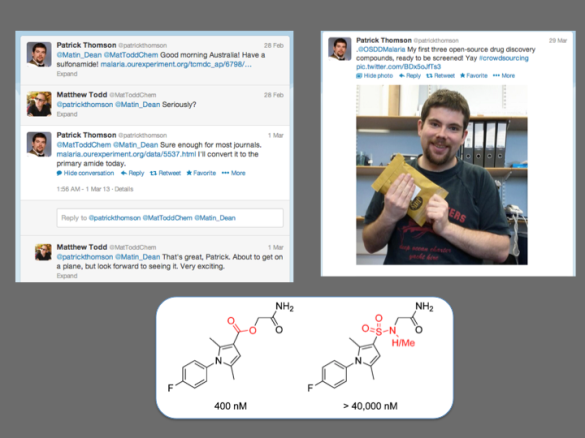

Because these difficulties were being tackled in real time, other scientists could read about them and suggest solutions. Patrick Thomson, an Edinburgh PhD student, was reading this and decided to join in. He got going in the lab on the sulfonamide sE, started posting his data to the same lab notebook the Sydney team were using (to make it easier to compare and share data) and started his own blog to help marshall and summarize results. He corresponded with a student in my lab in Sydney to overcome synthetic hurdles. Several of us worked together to ensure quality control of the data – simple in the digital age.

And Patrick nailed it. He made the compound. He then mailed it off for biological evaluation. Not to Sydney, which would be a waste of good funds for freight charges, but to a local lab at The University of Dundee. With the appropriate controls and sharing of all data, testing of compounds in different labs can be trusted to deliver a consistent picture.

In the event, Patrick’s molecules (he tested 3) were inactive. This is a shame, but at the same time the ester/sulfonamide replacement is an obvious one to make and the data enhance the paper where these results will go, on which Patrick will be an author.

Patrick showed great initiative here, and philosophical agility – he got involved with something unfamiliar where he had not met the people he’d be working with. Maybe it’s because he agreed with the principles of openness, or maybe it was because he saw that all project data were being shared so trust wasn’t an issue – he could see the project involved quality science. Either way, Patrick has provided an excellent example of how open source experimental lab-based research can work on a practical level.

Which makes one think of all sorts of added benefits of working in a genuinely open manner. One is that open source research provides a low-tech infrastructure for researchers from developing (endemic) countries to get involved in collaborative projects with their peers in the developed world. There are no expensive online tools, no subscription fees for software. Researchers carry out their work in local labs, and share all the data online using existing technology solutions. Crucially the mechanism scales because researchers interact directly, rather than having to pass everything by a bottleneck professor. There is no monolithic “aid” program needed, just the means for people to work together effectively and efficiently. The involvement of endemic labs remains to my mind a top priority target for open research – the barrier is identifying the labs with the right level of chemical facilities (if anyone has any ideas…).

Today the Open Source Malaria landing page is launched – the project used to be called Open Source Drug Discovery for Malaria, but the name was changed partly to highlight more the real essence of the project – open source. Much of the research is about basic synthetic chemistry, or biology and yes it’s aimed at finding new medicines for malaria, but at the same time the power of the approach lies in how it changes the way we do basic science. The new website highlights the most productive tools used thus far – the lab notebooks, the Github To Do list, the Twitter account, the wiki.

With these simple tools, Patrick was able to make an important, material contribution to an experimental research project without ever leaving his Wimbledon-winning home country. Anyone else can do the same if the inviolable principles of open source are agreed upon – No Need to Ask.

Bookmarks for July 18-20, 2013 | Evolving Newsroom 10:30 am on August 1, 2013 Permalink |

[…] An Example of Open Source Drug Discovery | Intermolecular […]

Crowdsourcing Drug Discovery | Intermolecular 10:44 pm on October 3, 2014 Permalink |

[…] Bookmarks for July 1… on An Example of Open Source Drug… […]

Open Source Malaria’s First Paper | Intermolecular 10:17 pm on September 14, 2016 Permalink |

[…] An Example of Open Source Drug Discovery July 15, 2013 […]