Rewards for Innovation, After the Fact

According to the family grapevine, I’m related to a pioneer of the industrial revolution. I’m the (great)n grandson of Samuel Crompton, inventor of the spinning mule that revolutionized textile production.

Portrait of Samuel Crompton by Charles Allingham (1788–1850), Bolton Library & Museum Services, Bolton Council, CC-BY-NC-ND

What I only recently learned is that Samuel didn’t patent his invention and was instead awarded some money, later, to recognize his contribution.

I was struck by this since it’s exactly what I’ve been writing about recently. A possible way of rewarding entrepreneurs who have worked, and shared, openly. Sustaining entrepreneurs who reject secrecy. A retrospective reward once something has demonstrated its importance and has impacted all our lives.

The story is related briefly in the Wikipedia article and more fully in a book. (French, Gilbert J. (1859). The Life and Times of Samuel Crompton, Inventor of the Spinning Machine Called the Mule. London: Simpkin, Marshall, and Company.)

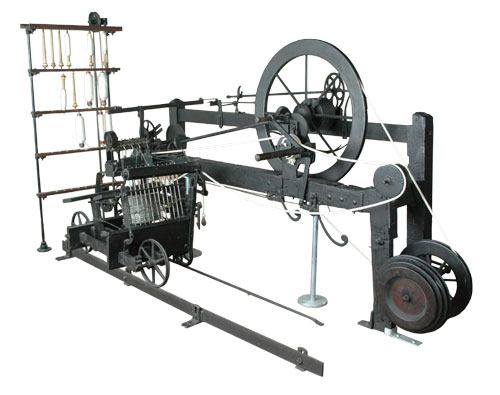

Samuel Crompton invented the mule, as an improvement on the jenny. The mule allowed for the production of fine cloths.

Spinning Mule, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mule-jenny.jpg

Samuel didn’t just invent this thing, he made one and actually started making superior cloth in his own home. The quality of the materials attracted a great deal of interest. People wanted to know how he was doing it and tried to ingratiate themselves into his house to see the machine in action. Someone even installed themselves in his attic and drilled a hole in the floor to try to peer through into the room below.

At this point Samuel was in possession of a trade secret. He knew it wouldn’t last. There was the possibility of patenting, but he could not afford this. He said to himself “a few months reduced me to the cruel necessity either of destroying my machine altogether or giving it up to the public. To destroy it I could not think of; to give up that for which I had laboured so long was cruel. I had no patent nor the means of purchasing one”.

Instead he tried a third way that I believe was sometimes used back then (late 18th Century England). In return for a cash contribution (a “subscription”) from a small number of individuals, he would reveal (to them) how the machine worked, and even give up the machine itself. Several people agreed and signed up. The information was duly handed over.

He never received a penny from anyone.

The information was presumably poorly guarded: the design flooded into the public domain, transforming (disrupting, as we would now say) the textile industry and contributing to the industrial might of the North of England (where I’m from, originally. My mother says that the statue of Samuel Crompton in Bolton looks exactly like my grandfather. I will need to investigate).

Statue of Samuel Crompton in Bolton, England. Copyright Kenneth Allen CC-BY-SA, http://www.geograph.org.uk/photo/980458

Samuel died not a rich man. Towards the end of his life the people of Bolton took this issue upon themselves, and raised a petition to parliament that complained Samuel had not received his dues. His invention had changed so much and made many people wealthy, while he was left with essentially nothing. A sum of 5 thousand pounds was awarded. This was seen as pitifully little, and somewhat insulting. Again, from the biography by French: “Thus after having haunted the lobby of the House of Parliament for five wearisome months in hourly expectation of his case being dealt with; leading a life of monotonous anxiety without variety or amusement of any kind … and day by day subjected to that ‘hope deferred which maketh the heart sick’, he returned home to Bolton with this phantom of national reward as the requital for his transcendent invention!”

An interesting situation, of which I would guess there are other examples. A novelty was created, and shared (essentially it “went generic” immediately) and the inventor was not rewarded.

I’m delighted in a way to discover this story. A terrible situation for my forebear, but intellectually fascinating for me as his descendant. I’m left reconsidering this question: is there a way we can work openly (i.e. no patents, no secrecy, no traditional “prizes” given these are typically secretive) and provide inventions to society (in a way that keeps costs down) while still incentivizing the innovators through rewards (i.e. after the fact, once the invention has clearly demonstrated its effectiveness).

I find this question interesting, particularly with respect to the discovery and development of new medicines. I’m reminded of the Health Impact Fund, in which research is done and medicines discovered and where the reward to the discoverer is calculated based on the demonstrated health benefits of the medicine. There is a very nice new representation of this idea by Rufus Pollock and colleagues in the iMed Project, in which it is made more clear that the R&D can be open source. I’m reminded of other kinds of “award” such as data exclusivity in which the R&D can be open and expenses can be reclaimed through the granting (again, from a government, on a piece of paper) of a temporary ability to set a medicine’s price at whatever you like once it’s helping people (a mechanism excitingly being tried by Al Edwards and colleagues in M4KPharma). The distribution of post facto awards to inventors requires high levels of either record keeping or trust or both. In open source everything is clearly laid out – who did what, who suggested what, who drove things forward. Maybe here there is a role for blockchain to industrialise trust – something others are, I think, already looking at.

Samuel Crompton’s story on the surface is one of an innovator not receiving his dues because he didn’t control his intellectual property effectively (he tried!). One can just say “well, so it goes”. But there is a clear, gut-feeling injustice here, and we’re left with a lingering sense of “surely there’s a better way of rewarding innovation that impacts society quickly because it is freely shared.” This makes me impatient to trial bold new funding proposals in real drug discovery and development projects.

Notes on further reading

1) Rufus Pollock’s essay on the evidence of patents as drivers of innovation in the industrial revolution.

Reply