SciFoo (and how about some more Science Unconferences)

I went to SciFoo this year. This is an invitation-only, 200-person event at Google HQ in Mountain View, organized by O’Reilly and Nature. I’d been invited before, only for it to clash badly with the start of the Sydney semester and the start of my teaching, cascading over me like a waterfall of incomplete handouts and practical demonstrations. Previously I’d caved. This time I didn’t and I flew to San Francisco just for the weekend. Oh man – am I glad I went.

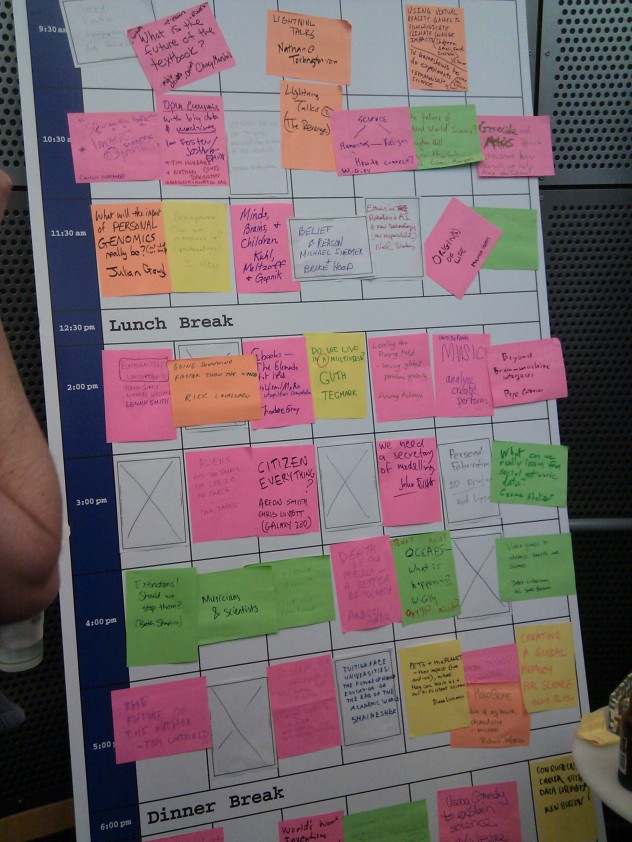

48 hours at the Googleplex. An intellectual lock-in. Nobody goes home. Nobody else comes through. It’s just them – and me. We all assembled, described ourselves to the crowd in three phrases, then wrote names of sessions we wanted to lead on post-it notes and stuck them on a grid of places and times. You grab a drink, and start talking. You stop talking when you can’t perceive your own soul anymore and need to sleep. I was jetlagged with a terrible cold that made me sound like my tonsils were made of sandpaper. But no matter.

So this is an “unconference” – something perhaps not familiar to many mainstream scientists. There is no pre-arranged agenda. You just get people together and let them talk about whatever they want. The schedule is made on the fly and can change. People with similar interests aggregate naturally. Through random chance or curiosity people who know nothing about the content of a session will show up.

This was the most inspiring meeting I’ve ever been to. The chemical content was next to zero. The science content was, well, it was just Proper Science, as it should be. Childish, naive, reaching for the stars. A succession of things that make you go “oooh that’s nice.” It was eyewateringly exciting. The naivety could have been annoying were it not for the fact that people invited are doing work so thoroughly marinaded in cool sauce and topped with awesomes and thousands.

The key to this success is simplicity – you just get good people. Organisers Tim O’Reilly, Timo Hannay and Chris DiBona know this very well. People the world over are doing the coolness – you just have to get them together. They then mutually remind each other why they got into science in the first place – it’s like motivational autocatalysis.

The tone was set on the first evening when Larry Page, at the end of his welcoming remarks said “You know, if what you’re doing isn’t going to change the world, then maybe you should do something else.” People kept referring to this over the next 48 hours, and it’s lodged in my brain ever since, gradually working its way to the centre.

Emily Brodsky talked for ten minutes in a Lightning Talks session about why one earthquake can trigger others. David Eagleman described how he’d dropped people off a crane to determine whether bullet-time was real. Noah Hutton gave a late-night session about a film he’s making on the Blue Brain Project, an attempt by Henry Markram to model a human brain in a computer in the next five years. Peter Singer caused a lot of discussion with his website that attempts to motivate people to donate money to charity. And so on and so on. The frustrating thing is not being able to go to all the parallel sessions. I still regret missing Yves Rossy talk about jet-propelling himself over the Channel.

The challenge when you’re there is to be able to explain how what you’re doing is going to change the world. It makes you think about your own work, and the work of the people around you. You’ve been invited because someone important (it’s never clear who) thinks that what you’re doing might well change the world. This forces you to forget about the detail we so often talk about, take a huge step back and confront the big picture lurking somewhere around you. Often at specialist science meetings, when challenged to talk about your work you might say “Well, I’m working in a calixarene-based sensor for [insert molecule]” or “I’m trying to make grantotoxin faster than this other guy” or “I do sesquiterpenes.” Technical, small answers to a technical crowd. That won’t do at a meeting like this.

On the first evening I was having a drink with a guy and Sergei Brin sidles up and asks me what I work on. My answer piqued his interest because I said “We’re working on making a drug needed in Africa by doing the science in the open, on the web, so that everyone can help us out and make the science go faster”. I got a lot of practice at permuting this kind of answer over the course of the next 50 times I was asked it. Everyone I spoke to liked the answer. Some people are doing similar things, like the truly wonderful Galaxyzoo project – their lead tech guy Arfon Smith was present. It was great to meet Michael Nielsen who made me aware that someone had already framed the concept of cognitive surplus – I’d been thinking about this ever since watching people play Tetris on their phones on Sydney buses and wishing that level of sustained concentration couldn’t be directed to a more meaningful goal.

I’ll never forget the first session. A few of us gathered in a room. I was sitting next to Will Noel, a guy putting ancient manuscripts online for the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore. The session was on “The Future of Space Travel”. An unassuming guy led it (can’t find who), and nobody was quite sure what to expect. He began by saying “So when I was flying the space shuttle…” and the room kind of changed – we all became little kids wanting to know what that was like.

It was a real pleasure to meet Derek Lowe at this meeting. Derek is a bellweather of pharma, and organic chemistry quite generally. A wise, considerate and articulate guy with a huge range of interests. We attended a session together where Lee Smolin explained what quantum gravity was. Waves (or particles) of Physics Envy crashed into me (again). Such big problems, concerning the nature of reality. Derek and I co-hosted a session on the possibility of Open Source Drug Discovery. A fascinating hour. I was able to brief everyone on what we are doing at the Synaptic Leap, where we’re trying to show we can open source process chemistry. The discussion turned to the rest of the drug discovery process, enormously facilitated by Derek’s wide-ranging expertise. The people in the room, from Creative Commons, from the White House, from industry were quick to clarify the thorny issues – but they all seemed to want the idea of OSDD to work – they all acknowledged something radical had to change in the coming years. I’ll have to return to this in a future post but the session was so inspiring. (I seem to share a lot of interests with Esther Dyson, who was in a lot of the sessions I went to. She was able to ask the best disruptive questions whilst spending most of the time apparently approving/rejecting friends on Facebook. Whatever works…)

Scifoo made me think about chemistry conferences a lot. I’ve been to a large number of chemistry conferences. I went to the American Chemical Society (ACS) meeting in San Francisco in March this year. I was at the conference venue the whole time the conference was on. I didn’t speak since I missed the abstract submission deadline that was sometime back in 1998 I think. I sat in sessions the whole time, I mingled and met all the people I wanted to, as well as a few people I hadn’t expected to. I had beer at the poster session and beers with people in the evenings. Was this conference a good use of my time? Apart some excellent beer conversations, not really.

There’s a separate post that’s needed here about where organic chemistry is, and where it’s going – a few people have been posting on this recently. But just in terms of the ACS meeting itself: with a few very notable exceptions the talks I saw were a) presented in a dull Powerpoint-heavy series of slides with verbal commentary about what was on the slides where even the presenter was visibly bored with what they were saying and b) on published material that was c) way too predictable and incremental. So both the presentational style and the content were disappointing. So many talks at the ACS would have been more interesting if the speaker had simply given out paper copies of their latest paper and given us 10 minutes to read it in silence then 10 minutes to talk about it. Now of course specialism necessitates incrementalism in content, but it’s no good if the meeting becomes a chore to sit and listen to. Nor is it good if the talks come out of the Powerpoint Machine (the genius of the “Chicken Talk” is that you can kind of follow the talk structure without listening to the content – it sounds exactly like most academic talks right up to the last supplementary slide in response to the second question at the end). In maybe 80% of the talks I attended nobody asked questions, or nobody was allowed to, or people asked “pity questions” just to break the awkward silence, but which were in no way interesting in themselves. So, constructive solutions:

1) people should be excited about what they’re presenting (there were a few excellent talks at the ACS I should add, by both faculty and students). If they’re not excited, they should sit back down.

2) conferences with little slots for questions, or where there are no questions, are of no real interest at all (particularly now that you can just listen to the talks online – a great move by the ACS)

3) how about we just scrap the schedule and allow people to talk on whatever they want on the day. Sessions have a title, which is a question or a hypothesis, and people come to discuss that without any pre-made slides. This removes the inanity of talks entitled “Recent Developments in X”

The ACS can deal with 2) and 3), not 1). While considering this, you may want to examine this picture of the control panel on the Google toilet cubicle wall.

and maybe this shot of the Google campus

Unconferences are the way forward. I hear that the Burning Man can be like this too (though from a look at the WP page it’s now huge). As can Maker Faire. So who’s on for a chemistry unconference, or maybe a chemistry/biology or chemistry/physics or chemistry/software unconference? (Gregynog and Gordon Conferences are close, but not quite there). Get good people together for a weekend. If you don’t want to actively participate, go somewhere else. Screw the usual formalities and just allow the day to pan out. There are no conference proceedings, and since you don’t actually present a series of slides, there’s nothing to put on your CV. Let the people who want to talk, talk, and see how the sessions define themselves, while insisting that sessions are framed around hypotheses. I wonder what would happen. Let’s try it. Sydney or London or New York or someplace nice.

Antony Williams 10:42 pm on October 25, 2010 Permalink |

Mat….I’m all for it! Yes, yes, yes. I;ve done Scifoo twice and truly enjoyed it and came away asking for more chemistry. Fortunately both times I was there I ended up hanging around with collaborators as well as meeting great new people. Many of the questions I carried with me to the conference remain unanswered though and I think a collective audience of chemists could really help. What can I do to help? When do we start ? 🙂

Jamie 11:03 pm on October 25, 2010 Permalink |

There are science unconferences… SciBarCamp. I’ve help organize these events in Toronto and Palo Alto. I’ve also heard of a Cambridge scibarcamp is in planning mode.

mattoddchem 11:08 pm on October 25, 2010 Permalink |

Jamie – I should have mentioned SciBarCamp explicitly – http://www.scibarcamp.org/. This came up when I asked the question here: http://ff.im/sbrlW. These are pan-science, right? Any theme?

Make quodlibets quotidian again! as scientific debates « Ceptional 8:17 pm on November 4, 2010 Permalink |

[…] answers were suggested by the master and others.” Sounds like a blend of the unconference (1,2) and what we think of as a traditional […]

The Open Science Unjournal « A quantum of science 8:38 am on December 11, 2010 Permalink |

[…] is an unjournal? An unjournal is to journals what an unconference is to conferences. To define what an unjournal is, take the first 2 sentences in the wikipedia […]